McIlwain-Nashimura, Margot.

Images in the Margins, The J. Paul Getty Museum and The British Library, 2009.

Images in the Margins is the third in the popular Medieval Imagination series of small, affordable books drawing on manuscript illumination in the collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum and the British Library. Each volume focuses on a particular theme and provides an accessible, delightful introduction to the imagination of the medieval world.

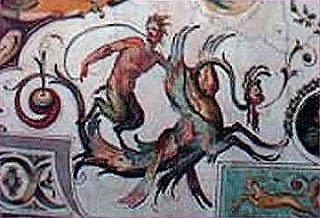

An astonishing mix of mundane, playful, absurd, and monstrous beings are found in the borders of English, French, and Italian manuscripts from the Gothic era. Unpredictable, topical, often irreverent, like the New Yorker cartoons of today, marginalia—images drawn in the margins of manuscripts—were a source of satire, serious social observation, and amusement for medieval readers. Through enlarged, full-color details and a lively narrative, this volume brings these intimately scaled, fascinating images to a wider audience.

Physiologus: A Medieval Book of Nature Lore, tr. Michael J. Curley, 2009. One of the most popular and widely read books of the Middle Ages, Physiologus contains allegories of beasts, stones, and trees both real and imaginary, infused by their anonymous author with the spirit of Christian moral and mystical teaching. Accompanied by an introduction that explains the origins, history, and literary value of this curious text, this volume also reproduces twenty woodcuts from the 1587 version. Originally composed in the fourth century in Greek, and translated into dozens of versions through the centuries, Physiologus will delight readers with its ancient tales of ant-lions, centaurs, and hedgehogs—and their allegorical significance. The woodcuts reproduced are from the 1587 Rome edition.

Panayotova, Stella, ed.

The Macclesfield Psalter, Thames & Hudson, 2008. Discoveries of real artistic treasures are exceptionally rare. The Macclesfield Psalter (c. 1335), a jewel of manuscript painting, was virtually unknown before its sale by Sotheby's in 2004. The manuscript offers a window into the medieval world, an intimate view of the faith, sentiments, prejudices, follies, and aspirations of medieval people. Doctors, minstrels, mummers, farmers, dancers, jesters, and beggars mingle on the pages as they would have done on the streets of a busy town. And the marginal imagery tempts the viewer to leave the confines of the prayer book and enter a wonderland of literary conceits, visions, and fables, with naked wild men, a dog dressed as a bishop, or a giant fish swimming across a page.

The Macclesfield Psalter is a revealing product of artistic and patronage exchange in the Middle Ages. A complete reproduction of the manuscript at its original size is accompanied by an authoritative text that not only interprets the textual and artistic content but also beguiles the reader through its vivid descriptions and rich insights.

Morrison, Elizabeth.

Beasts: Factual and Fantastic, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007.

Beasts Factual and Fantastic features vivid and charming details from the wealth of manuscripts in the collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum and the British Library, along with a lively text; together both word and image provide an accessible and delightful introduction to the imagination of the medieval world.

Barber, Richard.

Bestiary: Being an English Version of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Bodley 764, Boydell Press, 2006. Bestiaries are a particularly characteristic product of medieval England, and give a unique insight into the medieval mind. Richly illuminated and lavishly produced, they were luxury objects for noble families. Their three-fold purpose was to provide a natural history of birds, beasts and fishes, to draw moral examples from animal behaviour (the industrious bee, the stubborn ass), and to reveal a mystical meaning - the phoenix, for instance, as a symbol ofChrist's resurrection. This Bestiary, MS. Bodley 764, was produced around the middle of the thirteenth century and is of singular beauty and interest. The lively illustrations have the freedom and naturalistic qualityof the later Gothic style, and make dazzling use of colour. This book reproduces the 136 illuminations to the same size and in the same place as the original manuscript, fitting the text around them. Richard Barber's translation from the original Latin is a delight to read, capturing both the serious intent of the manuscript and its charm.

Mandeville, John.

The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, tr. C.W.R.D. Moseley, Penguin, 2005. Immediately popular when it first appeared around 1356, The Travels of Sir John Mandeville became the standard account of the East for several centuries—a work that went on to influence luminaries as diverse as Leonardo da Vinci, Swift, and Coleridge. Ostensibly written by an English knight, the Travels purport to relate his experiences in the Holy Land, Egypt, India, and China. Mandeville claims to have served in the Great Khan’s army and to have journeyed to “the lands beyond”—countries populated by dog-headed men, cannibals, Amazons, and pygmies. This translation by the esteemed C.W.R.D. Moseley conveys the elegant style of the original, making this an intriguing blend of fact and absurdity, and offering wondrous insight into fourteenth-century conceptions of the world. By the standards of the 14th century, the writing style of the man who called himself Sir John Mandeville is so informal as to be nearly chummy: "He who wants to pass over the sea to Jerusalem, may go by many ways, both by sea and by land depending on the countries he comes from; many ways come to a single end. But do not think I shall tell of all the towns and cities and castles that men shall go by, for then I must make too long a tale of it." Historians remain skeptical as to whether the author really did journey to the Holy Land and Egypt, or hire himself out as a soldier to the Great Khan of China. Whatever the case, it is indisputable that he is one of the first modern travel writers, as we have come to know the genre, and that his book was considered authoritative in matters geographical throughout Europe--consulted by Leonardo da Vinci and Christopher Columbus alike.

Camille, Michael.

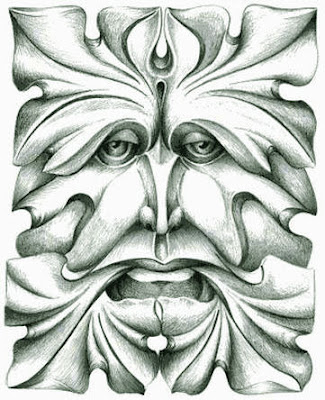

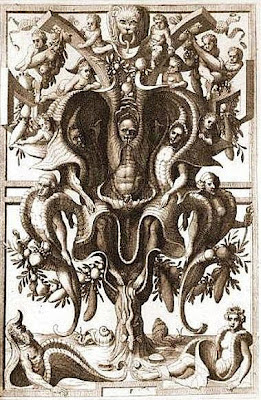

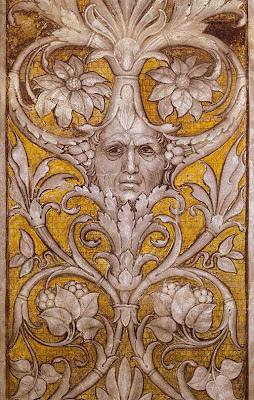

Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art, Reaktion Books, Essays in Art and Culture, 2004. What do they all mean – the lascivious ape, autophagic dragons, pot-bellied heads, harp-playing asses, arse-kissing priests and somersaulting jongleurs to be found protruding from the edges of medieval buildings and in the margins of illuminated manuscripts? Michael Camille explores that riotous realm of marginal art, so often explained away as mere decoration or zany doodles, where resistance to social constraints flourished. Medieval image-makers focused attention on the underside of society, the excluded and the ejected. Peasants, servants, prostitutes and beggars all found their place, along with knights and clerics, engaged in impudent antics in the margins of prayer-books or, as gargoyles, on the outsides of churches. Camille brings us to an understanding of how marginality functioned in medieval culture and shows us just how scandalous, subversive, and amazing the art of the time could be.

Bildhauer, Bettina, and Robert Mills, eds.

The Monstrous Middle Ages, University of Toronto Press, 2004. The figure of the monster in medieval culture functions as a vehicle for a range of intellectual and spiritual inquiries, from questions of language and representation to issues of moral, theological, and cultural value. Monstrosity is bound up with questions of body image and deformity, nature and knowledge, hybridity and horror. To explore a culture's attitudes to the monstrous is to comprehend one of its most important symbolic tools.

The Monstrous Middle Ages looks at both the representation of literal monsters and the consumption and exploitation of monstrous metaphors in a wide variety of high and late-medieval cultural productions, from travel writings and mystical texts to sermons, manuscript illuminations and maps. Individual essays explore the ways in which monstrosity shaped the construction of gender and sexual identity, religious symbolism, and social prejudice in the Middle Ages. Reading the Middle Ages through its monsters provides an opportunity to view medieval culture from fresh perspectives. The Monstrous Middle Ages will be essential reading for anyone interested in the concept of monstrosity and its significance for both medieval cultural production and contemporary critical practice.

Bovey, Alixe.

Monsters and Grotesques in Medieval Manuscripts, University of Toronto Press, 2002. The margins of medieval manuscripts teem with sirens, satyrs, griffins, unicorns, dragons and other bizarre creatures. Commonplace animals are twisted together in impossible combinations, and human bodies are merged with animal forms in ways that are often both comic and ghastly. Images of these monstrosities pervade art and culture in the Middle Ages, and for medieval people they must have been a tantalizing suggestion of unknown worlds and unthinkable dangers. But what were they doing there? Were they meaningless distractions, or did these strange beasts have other symbolic meanings? Alixe Bovey's thoroughly readable text explains the meaning of these monsters and their place in medieval art.

Friedman, John Block.

The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought, Syracuse University Press, 2000.

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome.

Of Giants: Sex, Monsters and the Middle Ages, University of Minnesota, Center for Medieval Studies, Medieval Cultures, Vol. 17, 1999.

Camille, Michael.

Mirror in Parchment: The Luttrell Psalter and the Making of Medieval England, University of Chicago, 1998. What is the status of visual evidence in history? Can we actually see the past through images? Where are the traces of previous lives deposited? Michael Camille addresses these important questions in Mirror in Parchment, a lively, searching study of one medieval manuscript, its patron, producers, and historical progeny. The richly illuminated Luttrell Psalter was created for the English nobleman Sir Geoffrey Luttrell (1276-1345). Inexpensive mechanical illustration has since disseminated the book's images to a much wider audience; hence the Psalter's representations of manorial life have come to profoundly shape our modern idea of what medieval English people, high and low, looked like at work and at play. Alongside such supposedly truthful representations, the Psalter presents myriad images of fantastic monsters and beasts. These patently false images have largely been disparaged or ignored by modern historians and art historians alike, for they challenge the credibility of those pictures in the Luttrell Psalter that we wish to see as real. In the conviction that medieval images were not generally intended to reflect daily life but rather to shape a new reality, Michael Camille analyzes the Psalter's famous pictures as representations of the world, imagined and real, of its original patron. Addressed are late medieval chivalric ideals, physical sites of power, and the boundaries of Sir Geoffrey's imagined community, wherein agricultural laborers and fabulous monsters play a similar ideological role. The Luttrell Psalter thus emerges as a complex social document of the world as its patron hoped and feared it might be.

Benton, Janetta Rebold.

Holy Terrors: Gargoyles on Medieval Buildings, Abbeville, 1997. The true gargoyle is a waterspout, an architectural necessity that medieval artisans transformed into functional fantasies. In clear, lively language, the introduction to Holy Terrors explains everything that is known about the history, construction, and purposes of these often rude and rowdy characters. The three chapters that follow are devoted to the gargoyles themselves, in human, animal, and grotesque form. Delving into their sometimes funny, sometimes mysterious meanings, Dr. Benton's entertaining text puts these irresistible creatures into the context of medieval life, and she provides a guide to gargoyle sites, so that readers can visit their favorites. This is, amazingly, the first book for adults to provide a full overview of medieval gargoyles, and it is bound to increase the already numerous legions of gargoyle admirers.

Benton, Janetta Rebold.

The Medieval Menagerie: Animals in the Art of the Middle Ages, Abbeville, 1992. Featuring incredible creatures and grotesque gargoyles, "The Medieval Menagerie" takes us from the improbable to the impossible as it traces the depiction and the meaning of real and imaginary animals in medieval art. From unicorns and dragons to elephants, lions, and monkeys, medieval society was fascinated with animals, whether they actually existed or not. The more fantastic the creature, the greater its hold seems to have been on the fertile imaginations of the Middle Ages. Both art and literature abound with vividly concocted examples of Gothic monsters (gargoyles and griffins), bizarre ideas about real if exotic beasts (lions were believed to be born dead and resurrected by the father lion three days later), and strange visions of composite creatures (such as a widely accepted animal believed to be a cross between an ant and a lion). Featuring the celebrated collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, "The Medieval Menagerie" is illustrated with the splendid and amusing beasts found in medieval painting, sculpture, architecture and decorative arts, as wello as in bestiaries and manuscripts. The text explores the depiction and the meaning of real and imaginary animals in medieval art.

__

Borges, Jorge Luis.

The Book of Imaginary Beings (

El libro de los seres imaginarios, 1967), tr. Andrew Hurley, Penguin, 2006. In a perfect pairing of talent, this volume blends twenty illustrations by Peter Sís with Jorge Luis Borges's 1957 compilation of 116 "strange creatures conceived through time and space by the human imagination," from dragons and centaurs to Lewis Carroll's Cheshire Cat and the Morlocks of H. G. Wells's The Time Machine. A lavish feast of exotica brought vividly to life with art commissioned specifically for this volume, The Book of Imaginary Beings will delight readers of classic fantasy as well as Borges's many admirers.

The master, writing with sometime collaborator Guerrero, compiled 82 one- and two-page descriptions of everything from "The Borametz" (a Chinese "plant shaped like a lamb, covered with golden fleece") to "The Simurgh" ("an immortal bird that makes its nest in the tree of science") and "The Zaratan" (a particularly cunning whale) in An Anthology of Fantastic Zoology in 1954. He added 34 more (and illustrations) for a 1967 edition, giving it the present title, and it was published in English in 1969. This edition, with fresh translations from Borges's Collected Fictions translator Hurley, and new illustrations from Caldecott-winner Sís, gives the beings new life. They prove the perfect foils for classic Borgesian musings on everything from biblical etymology to the underworld, giving the creatures particularly (and, via Sís, whimsically) vivid and perfectly scaled shape. "We do not know what the dragon means, just as we do not know the meaning of the universe," Borges (1899–1986) and Guerrero write in a preface, and the genius of this book is that it seems to easily contain the latter within it.

Asma, Stephen T.

On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears, Oxford University Press, USA, 2011. Real or imagined, literal or metaphorical, monsters have exerted a dread fascination on the human mind for many centuries. Using philosophical treatises, theological tracts, newspapers, films, and novels, author Stephen T. Asma unpacks traditional monster stories for the clues they offer about the inner logic of our fears and fascinations throughout the ages. Asma's book zooms in on the subject of monsters, both mythical and real, past, present and future, detailing how they have fascinated and frightened the human imagination through all of recorded time. Conjuring dread, the mind's eye has embraced the Philistine giant Goliath, Grendel, the golem of Jewish lore, Frankenstein's monster, freak shows, monster spectacles and werewolves with equal parts affection and terror, writes Asma, a philosophy professor at Columbia College Chicago. Using varied media sources, from history to legend and literature, Asma studies the symbolic meaning of monsters (e.g., biblical monsters represent arrogance in the face of God's power) and their psychological function. He concludes that humans need an excuse to fight, protect and defend, as well as to transfer those horrific qualities, our own monstrous desires, to inhuman beings. A wide-ranging exploration of fear and evil, Asma's presentation and theories are original and practical, depicting those dark, repulsive notions of an unstable, turbulent world in which everybody must struggle to remain human and civilized. Hailed as "a feast" (Washington Post) and "a modern-day bestiary" (

The New Yorker), Stephen Asma's On Monsters is a wide-ranging cultural and conceptual history of monsters--how they have evolved over time, what functions they have served for us, and what shapes they are likely to take in the future. Beginning at the time of Alexander the Great, the monsters come fast and furious--Behemoth and Leviathan, Gog and Magog, Satan and his demons, Grendel and Frankenstein, circus freaks and headless children, right up to the serial killers and terrorists of today and the post-human cyborgs of tomorrow. Monsters embody our deepest anxieties and vulnerabilities, Asma argues, but they also symbolize the mysterious and incoherent territory beyond the safe enclosures of rational thought. Exploring sources as diverse as philosophical treatises, scientific notebooks, and novels, Asma unravels traditional monster stories for the clues they offer about the inner logic of an era's fears and fascinations. In doing so, he illuminates the many ways monsters have become repositories for those human qualities that must be repudiated, externalized, and defeated.

Kearney, Richard.

Strangers, Gods and Monsters: Interpreting Otherness, Routledge, 2002. Strangers, Gods and Monsters is a fascinating look at how human identity is shaped by three powerful but enigmatic forces. Often overlooked in accounts of how we think about ourselves and others, Richard Kearney skilfully shows, with the help of vivid examples and illustrations, how the human outlook on the world is formed by the mysterious triumvirate of strangers, gods and monsters. Throughout, Richard Kearney shows how Strangers, Gods and Monsters do not merely reside in myths or fantasies but constitute a central part of our cultural unconscious. Above all, he argues that until we understand better that the Other resides deep within ourselves, we can have little hope of understanding how our most basic fears and desires manifest themselves in the external world and how we can learn to live with them.

Gilmore, David, D.

Monsters: Evil Beings, Mythical Beasts, and All Manner of Imaginary Terrors, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009. The human mind needs monsters. In every culture and in every epoch in human history, from ancient Egypt to modern Hollywood, imaginary beings have haunted dreams and fantasies, provoking in young and old shivers of delight, thrills of terror, and endless fascination. All known folklores brim with visions of looming and ferocious monsters, often in the role as adversaries to great heroes. But while heroes have been closely studied by mythologists, monsters have been neglected, even though they are equally important as pan-human symbols and reveal similar insights into ways the mind works. In

Monsters: Evil Beings, Mythical Beasts, and All Manner of Imaginary Terrors, anthropologist David D. Gilmore explores what human traits monsters represent and why they are so ubiquitous in people's imaginations and share so many features across different cultures. Using colorful and absorbing evidence from virtually all times and places,

Monsters is the first attempt by an anthropologist to delve into the mysterious, frightful abyss of mythical beasts and to interpret their role in the psyche and in society. After many hair-raising descriptions of monstrous beings in art, folktales, fantasy, literature, and community ritual, including such avatars as Dracula and Frankenstein, Hollywood ghouls, and extraterrestrials, Gilmore identifies many common denominators and proposes some novel interpretations. Monsters, according to Gilmore, are always enormous, man-eating, gratuitously violent, aggressive, sexually sadistic, and superhuman in power, combining our worst nightmares and our most urgent fantasies. We both abhor and worship our monsters: they are our gods as well as our demons. Gilmore argues that the immortal monster of the mind is a complex creation embodying virtually all of the inner conflicts that make us human. Far from being something alien, nonhuman, and outside us, our monsters are our deepest selves.

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome.

Monster Theory: Reading Culture, Univiversity of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Psalters—books containing the Psalms from the Bible, usually decorated and illustrated—were common in the Middle Ages. They were intended for the private use of a family; a wealthy one, since the production of an illuminated psalter was expensive and time-consuming.

Psalters—books containing the Psalms from the Bible, usually decorated and illustrated—were common in the Middle Ages. They were intended for the private use of a family; a wealthy one, since the production of an illuminated psalter was expensive and time-consuming.